Revival package doesn’t help the poor or middle class, backbone of India’s

broken economy

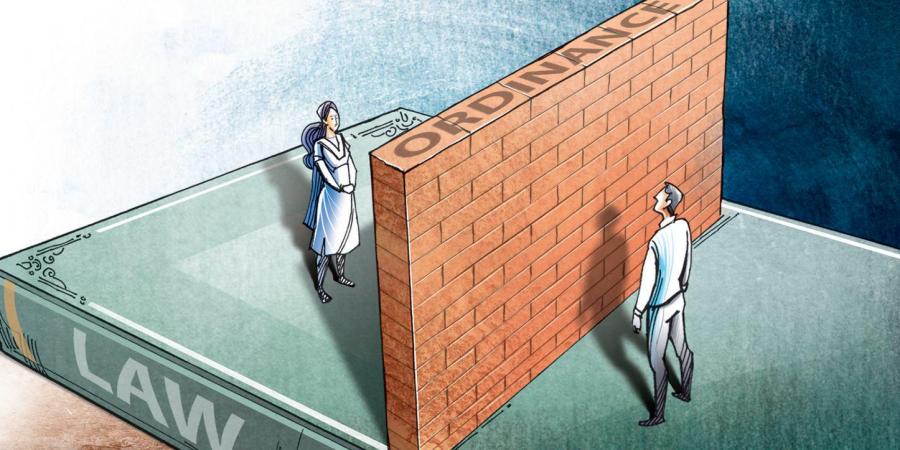

Justice is at the heart of all human endeavour. This pandemic has taken us all by surprise. The task of a responsive government is to ensure the economic survival of diverse interests. Our nation’s economy, bueted by this pandemic, must be protected not by knee-jerk reactions but thoughtful decisions embedded in equity.

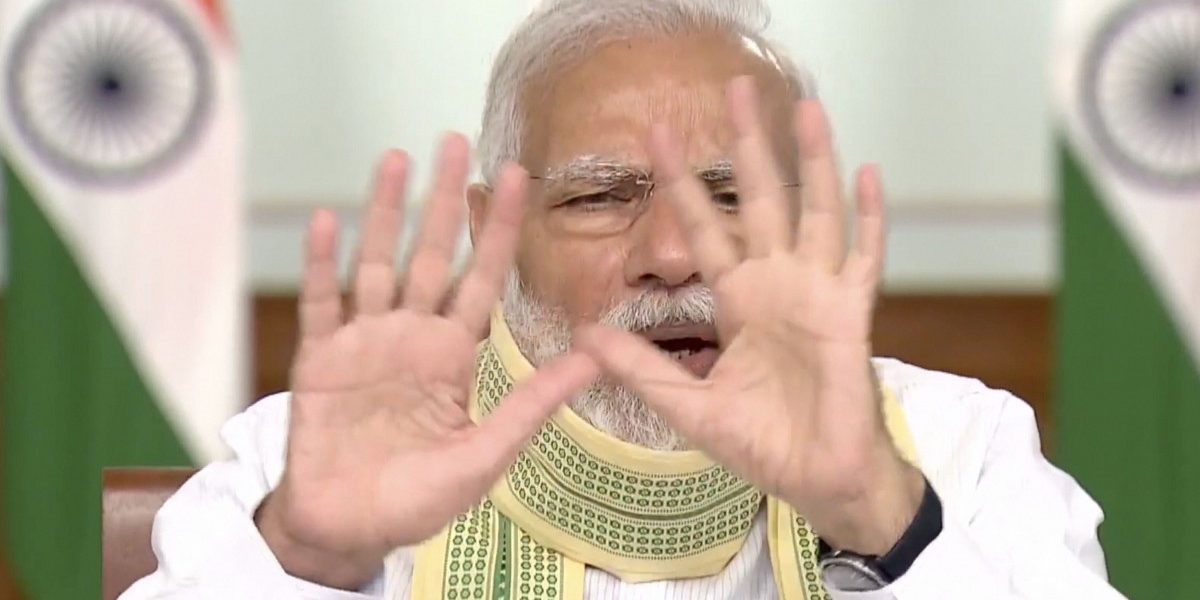

The Rs 20 lakh crore package announced by Prime Minister Narendra Modi and delivered intranches by nance minister Nirmala Sitharaman, doesn’t address the real problems the economy faces. This package is nowhere near 10% of India’s GDP, as claimed. Analysts peg it

at about 1% of GDP. Before March 24, when Modi announced the lockdown, our economy was already stuttering. There is nothing in the economic package catering to the needs of a selfreliant India, which requires world class infrastructure, ecient bureaucratic systems and

skilled human resource. On all these fronts, we are wanting.

The basic aw is in the direction of the package. More than a revival package, what’s desperately needed is a survival package for the poor and small businesses. The rst tranche catered to credit availability. Neither additional working capital loans nor subordinate debt for businesses including MSMEs are the right prescription in the absence of robust consumer demand.

In any case, a large number of MSMEs are excluded since they have not borrowed from formal channels like banks and NBFCs. Neither are likely to provide debt to promoters to put into already stressed MSMEs. Providing liquidity to discoms, a repackaging of the failed UDAY, will

not cater to economic revival. Capital is required to generate and satisfy demand. Access to capital in the absence of demand is a risky proposition. The second tranche allowed something for the needy. Free food grain supply for migrants for two months will be dicult to implement given that thousands are waiting to reach home.

The rest of the measures are futuristic.

Access to PDS rations from fair price shops by March 2021, with the concept of one nation one ration card, has little to do with the present crisis. It is the repetition of an initiative announced in January to be realised by June 2020.

Credit facility to street vendors; aordable rental housing under PPP for migrants and urban poor; boost to the housing sector indicated that the nance minister was clueless about solutions required today, in situ, to alleviate the misery of the poor. Farm-gate infrastructure for farmers; a scheme for formalisation of micro-food enterprises, a scheme for shermen, all included in the third tranche, fell far short of what is needed now.

The fourth tranche too consisted of policy prescriptions to deal with commercial mining, defence production and tari reforms in the power sector with privatisation of distribution in view. The fth tranche increased the allocation for MGNREGA, the only silver lining within the cloudy and unfocussed vision of this government.

One felt that the FM was presenting a fresh budget along with o budget policy A doctor needs to revive a patient in the emergency ward by administering medicine to help him survive. It’s no good telling him that he will survive if structural changes are carried out in the hospital premises reforms.

Despite these announcements, the RBI thinks growth this year will be in the negative territory and various sectors of the economy will continue to face acute stress. It was, however, touching of the FM to share the pain of the migrants walking hundreds of kilometres,

and oer them nothing apart from the promise of food grains for comfort.

The pandemic has left a large underbelly of poverty stricken people. The movement of 4.6 crore migrants has exposed us to the prevailing massive scales of poverty. 93% of our workforce including migrants being in the informal sector, without security of jobs, is a reection

of an economy where millions live on the margins. A recent survey conducted by Stranded Workers Action Network (SWAN) of 11,000 migrant workers, indicated that 86% of them had not been paid by their employers during the lockdown, and 96% received no food from the government.

The ILO Report 2020 suggests that 400 million workers employed in the informal economy are at risk of falling deeper into poverty during this crisis. Unemployment, which rose to 8.4% on March 22, increased to 27.4% by April 5. The rate of unemployment in urban India reached

24.95% and in rural India 22.89% (CMIE Report). In aviation and tourism alone, job losses of 38 million represent 70% of the total workforce (KPMG). In the textile and apparel sector, 2.5 to 3 million job losses have occurred because of order cancellations.

It is estimated that over 136 million non-agricultural jobs are at immediate risk, the most vulnerable being workers without formal employment, contractual workers, casual labour, those working in small companies and the self-employed. Casual labour, which forms 25% of

the total workforce, are the rst to be hit by the lockdown. In the construction industry, they form 83% of the workforce. With real estate in dire straits, their plight should be a matter of national concern.

Faced with a bleak future, apart from layos, companies across sectors are imposing salary cuts of 15-40% for the remaining sta. What we don’t need now are long-term solutions. A doctor dealing with a patient in the emergency ward needs to revive him by administering

medicine to help him survive. It’s no good telling him that he will survive if structural changes are carried out in the hospital premises. These packages oer nothing for the migrant, the informal sector, the poor or even the middle class – the backbone of the Indian

economy. Supply side solutions are the wrong medicine to administer in the midst of the pandemic.

The PM and FM have sold another dream. Only time will tell whether the poor and middle class will again be misled by yet another ‘jumla’.