We are in the midst of a national crisis. With extended lockdowns, our paralysed economy is in a wait-and-watch mode. The poor have been hit the hardest. The plight of migrants is heart-wrenching. The facilities provided at the so-called “shelters” are woefully inadequate in terms of food, sanitation, toilets and medical care. Over 400 million people in the informal sector have no means of livelihood. It is for the executive to take appropriate measures, by honouring its statutory obligations, to ensure that their constitutional rights are not trampled upon. Under our constitutional framework, the executive is answerable even in times of a national crisis. It may not be constitutionally appropriate to believe that the executive knows “best” in times of crises. It never does. Otherwise, we would not have courts of law.

Of course, courts may not interfere with economic packages the government announced for helping those affected by the pandeic.m That is in the exclusive domain of the executive. But if the impact of executive decisions hurts those who have, in such situations, no recourse to courts of law, then the judiciary must sit up and ensure that laws are obeyed. Take, for example, the state of these “shelters”. Under the Disaster Management Act, 2005 (Act of 2005), a National Disaster Management Authority (NDMA) presided over by the prime minister with nine nominees of the government is obliged to lay down guidelines for minimum standards of relief to be provided in relief camps in relation to shelter, food, drinking water, medical cover and sanitation (Section 12). It also provides for ex-gratia assistance on account of the loss of life, for the restoration of means of livelihood and other reliefs. If the NDMA has not issued such guidelines, how will the executive be made accountable?

Migrant workers stranded mid-way between the place where they are sheltered and their homes have protested in frustration. We have witnessed and heard the stories of our citizens walking hundreds of kilometres to reach home. The state has not provided them with transportation. The fact that they have chosen to walk such long distances is proof enough of state apathy or inefficiency. To ensure that such facilities are made available is the only way the court can make the executive accountable. If courts look the other way, the executive will have a free run. Even in times of war, the Constitution is not silent. All institutions in emergencies must respect, to the extent possible, the fundamental rights of citizens. There is enough material to suggest that these rights have been, prima-facie, violated.

Even if courts were not to interfere, the least they must do is to direct that the government places before the court data concerning all actions conforming to the executive’s constitutional and statutory obligations. That will serve two purposes. One, measures the government has taken thus far will become a matter of record. Two, the manner and extent to which its decisions have been implemented will have to be demonstrated. All actions of the NDMA will thus be under scrutiny. That, in turn, will at least assure people that the courts’ oversight might help mitigate their suffering. This will allow non-state actors to verify government claims.

Recently, the PM established the Prime Minister’s Citizen Assistance and Relief in Emergency Situations (PM-CARES) fund to which the private sector can contribute monetarily. The objective of the fund is to alleviate the pain of those affected by the pandemic. The setting up of a National Disaster Response Fund (NDRF) under the Act of 2005 (section 46) is for the same purpose. Any person or institution can make contributions into such a fund for mitigation. The NDRF is to be utilised by the National Executive Committee (NEC) to address the emergency response, relief and rehabilitation per the guidelines laid down by the central government in consultation with the NDMA (section 46). The provisions of the Act of 2005 override all other laws or administrative actions of the government (section 72).

THE pure legal issue is whether a fund called PM-CARES can be created by setting up a trust when the Act of 2005 provides otherwise. If the contributions were to the NDRF, then the NEC will deal with it consistent with the needs arising out of this emergent situation. No individual will get credit for it. Who else, except the judiciary, will scrutinise this decision of the central government?

Other decisions of the executive including those directing employers to pay salaries of employees during the lockdown period also require judicial scrutiny since no provision of the Act of 2005 empowers the NEC to so direct.

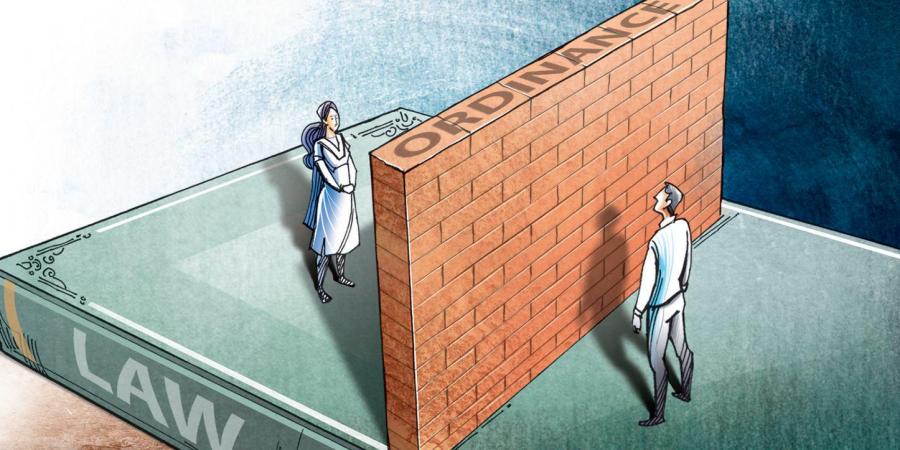

Courts are sentinels of the Constitution. The Constitution is like a fort within which institutions play their assigned roles. A display of attrition between institutions is a healthy sign. The bonhomie between institutions or the judiciary’s hands-off approach will make the fort crumble. Silence within the fort is proof that no one is left to protect the Constitution.